The entrepreneur is essentially a visualizer and an actualizer.

He

can visualize something, and when he visualizes it he sees exactly how to make it happen.

- Robert L. Schwartz

Luigi Nocivelli,

an unforgettable story

Luigi Nocivelli was a great Italian

entrepreneur from the second half of the Twentieth century, and a great man. An individual akin to

a Renaissance man; he managed to bring together the two sides of his

personality, combining a love of mechanics with art, industry with agriculture, architecture with

literature, and technological innovation with respect for nature.

His entrepreneurial approach was one of dedication, skill, organisation,

curiosity and practicality. His ability to bring projects to

life resulted in the small family workshop being transformed into Ocean. He was both Managing Director and Chairman of Ercole Marelli in the seventies, and created an electrical appliance

empire in the Eighties and Nineties. He briefly worked at the very top of Moulinex

in 2000-2001, before going on to found the Epta Group in

2003.

Just like young Hans Castorp in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, his favourite novel, Luigi Nocivelli was

a man ‘favoured by life’, who would imagine his future and work with all his might to turn it into

reality. Order, humility, resilience and the ability to hand over the

reins: these were the values he never abandoned. Luigi Nocivelli had many accomplishments, but

also lived through moments of great difficulty, before dusting himself off and standing back up driven by

courage and perseverance, launching himself into new adventures that would prove his worth as an

individual and as a businessman.

Human reason needs only to will more strongly than fate, and she is fate.

- Thomas Mann

from 1930 to 1956:

Youth

Luigi Nocivelli was born in Offlaga, in the plains of the Brescia region of Italy, on April 29th, 1930. He

was the firstborn son of Angelo and Orsola (known as Lina) Nocivelli. His mother came from a middle class

local family that included several aristocratic relatives, as well as professionals such as lawyers,

notaries, doctors and pharmacists. The Nocivelli family originally hailed from a small village outside

Parma, in the municipality of Pellegrino Parmense, called (funnily enough) Nocivelli. For many generations

they sold textiles, but at the end of the First World War Angelo

Nocivelli and his brother Lorenzo decided to become electricians. It

was cutting-edge work in those years, at the very dawn of electricity. Angelo was initially employed as a

blue collar worker at Engineer Malfassi’s electrical company in Verolavecchia, in the province of Brescia, before he decided to go into

business on his own. For the most part he repaired and installed small electrical systems and rewound

motors and transformers.

In the nineteen-forties, Angelo Nocivelli built his own electromechanical workshop, in which his children

occasionally worked. The newly minted entrepreneur headed to the Trade Fair

on June 28th, 1947 with his sons Luigi and Enrico. It was the first large-scale event to be staged in Milan after

the War, and was hailed as a not-to-be-missed appointment with industry, research and innovation. But

during that fateful train journey, the train jolted and Angelo lost his balance from his seat on the

flatbed of one of the wagons, falling off the train and seriously injuring himself. Luigi, who was about to get his diploma as

an industrial electrical engineering technician, had to keep the

family business going during his father’s long convalescence. These were two tough years with

much uncertainty, but they proved decisive to forming the character and personality of Luigi Nocivelli.

This period reinforced his willpower, his technical skills, his passion for

mechanical and electromechanical engineering and his ability to fight

with all his might to achieve his goals.

Early in the year 1950, Angelo Nocivelli’s health improved and he

resumed working with his son. Luigi Nocivelli decided to continue his studies as well, enrolling in the

faculty of Business and Economics at Milan’s Bocconi University. He

never finished University, but was a keen student in his law and statistics courses. One day, whilst

waiting for lessons to begin, he read an article about voltage

regulators that Siemens had designed but never produced on an industrial scale, and had a flash

of inspiration. This component improved the viewing quality of televisions, which were rapidly spreading

throughout Italy, and a regulator would be needed for every set sold. The potential market was huge. The

curiosity Luigi would have throughout his life, prompting him to

explore, examine and seek new ideas in search of constant innovation,

laid the foundation for his first success, as the Nocivelli family began making regulators for television

sets. The family workshop began to grow. Autovox was the first major

customer working throughout Italy, and both demand and production quickly increased – the business needed

to grow.

Early in the year 1950, Angelo Nocivelli’s health improved and he

resumed working with his son. Luigi Nocivelli decided to continue his studies as well, enrolling in the

faculty of Business and Economics at Milan’s Bocconi University. He

never finished University, but was a keen student in his law and statistics courses. One day, whilst

waiting for lessons to begin, he read an article about voltage

regulators that Siemens had designed but never produced on an industrial scale, and had a flash

of inspiration. This component improved the viewing quality of televisions, which were rapidly spreading

throughout Italy, and a regulator would be needed for every set sold. The potential market was huge. The

curiosity Luigi would have throughout his life, prompting him to

explore, examine and seek new ideas in search of constant innovation,

laid the foundation for his first success, as the Nocivelli family began making regulators for television

sets. The family workshop began to grow. Autovox was the first major

customer working throughout Italy, and both demand and production quickly increased – the business needed

to grow.

In 1956 Luigi was drafted into military service, but even while serving in the armed forces he continued

to mull over how to develop the family business. His goal was to transform it into a fully-fledged

electromechanical factory. Shortly after being discharged, in December 1957,

Ocean was established in Verolanuova in a plant measuring over one

thousand square metres in Via Mazzini. The name was an acronym for “Officina Costruzioni Elettriche

Angelo Nocivelli”, or Angelo Nocivelli Electrical Construction Factory.

It’s not true that it is the researcher who pursues the truth, it is the truth that pursues the researcher.

- Robert Musil

1957:

Ocean

Ocean was founded in 1957, but just a few months in the business was

booming. The company was run by Angelo

and Luigi, along with his sister Bruna, who handled the

administration and Gianfranco, who specialised in sales relations and

would continue working with his brother Luigi in all their later endavours. Nonetheless, in 1958 the

regulator market suddenly collapsed: Philips had patented an

electronic device to be housed inside the television set, thereby removing the need for external

regulators. In the space of a few months, all of its competitors were following suit.

Luigi Nocivelli did not lose heart, and instead turned this difficult moment into an opportunity to diversify the family business. He decided to explore refrigeration, a market that was new at the time and growing fast also

thanks to companies like Motta and Alemagna, which were specialising in ice cream production. In 1959, Ocean started producing a small range

of freezers. To optimise costs, they decided to fold the metal sheets at a sharp angle, running

against the trend of the time, which favoured soft, rounded angles. This was a decision that proved to be

a step ahead of a later trend, which would link structured, angular shapes with a perception of modernity

and technological efficiency. Luigi forged ties with a number of electromechanical components producers,

and embarked on a long phase of experimentation with prototypes. The first few months were almost entirely

dedicated to perfecting the complex cooling system. The greatest

problem posed was the size of the system, and the amount of freon to be used. Once the right balance had

been struck, work got underway with a complete industrial production

line. The regulators made way for refrigerators at Ocean in Via

Mazzini, which had expanded with a new warehouse measuring over one

thousand square metres. The first customers were mostly local dealers in the industrial

production of ice cream brands, quickly joined by sellers of soft drinks. At the outset the market was

limited to Italy, but as soon as 1960 sales grew to over 5,000 pieces.

That same year, Luigi Nocivelli married Barbara Zarnetti. In 1964,

the couple and their children moved inabove the new ten thousand square

metre Ocean plant in Viale Europa, also in Verolanuova. The Company expanded considerably,

reaching beyond the Italian borders. Thanks to the skill of both Luigi and Gianfranco, Ocean became one of

Europe’s leading sub-contracted freezer manufacturers, with production reaching 250,000 pieces a year.

That same year, Luigi Nocivelli married Barbara Zarnetti. In 1964,

the couple and their children moved inabove the new ten thousand square

metre Ocean plant in Viale Europa, also in Verolanuova. The Company expanded considerably,

reaching beyond the Italian borders. Thanks to the skill of both Luigi and Gianfranco, Ocean became one of

Europe’s leading sub-contracted freezer manufacturers, with production reaching 250,000 pieces a year.

In 1969 the Nocivelli family bought a further plant measuring around

10,000 square metre in Pozzaglio (in the province of Cremona, 7.3 km

away) to manufacture vertical freezers for domestic use. In Viale Mazzini they produced roll-bond

cabinets, using the cooling system taken from Ocean products. This system featured a cutting-edge core of

two aluminium sheets enveloping the serpentine in which the cooling fluid circulated. The roll-bond

cabinets for horizontal freezers were then moved to the plant in Viale Europa, where the products were

fully assembled.

Luigi Nocivelli was an unusual businessman: he himself had been an apprentice and blue-collar worker, a

technician and a man of vision and intuition. He enjoyed manual work

and would often go onto the production floor to take over from employees for the sheer enjoyment of being

an integral part of the process. Ocean developed in keeping with his character and skills, complemented by

those of his brother Gianfranco.

Life and dreams are leaves from the same book.

- Arthur Schopenhauer

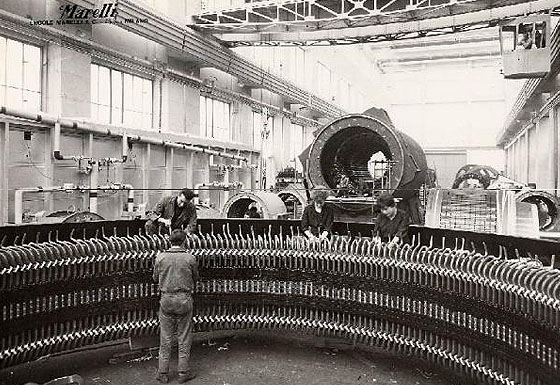

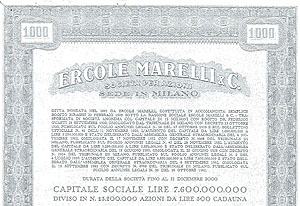

1973:

At the helm of Marelli

In the early seventies, while Ocean continued to grow, Luigi Nocivelli was nurturing a dream to launch

Italian electrical appliances on an international scale. Between 1971

and 1973, he embarked on a silent process to buy up shares of Ercole

Marelli, without ever declaring it in public. With true determination he worked his way to the

top of the company which, more than any other, represented Italy’s large potential in the sector. He only

came out into the open once he had acquired 30% of the shares, and in

1973* he joined the Board of Directors as the majority

shareholder and took control of the company, leaving the task of guiding Ocean in the hands of

his brother Gianfranco.

When Luigi Nocivelli joined the company, he found a far worse situation than he had expected from the

outside. Ercole Marelli was heavily indebted, the group’s structure was obsolete, the longer-serving managers enjoyed

long-standing privileges and the departments were followed outdated industrial models. The situation among younger employees was no

better. Many has been hired in the wake of political agreements, a large number were barely schooled, some

were members of armed political movements and barely concealed their work with far-left groups within the

factory. One such person was Walter Alasia, of Red Brigades fame. For the past fifteen years, the company had been immobilised, with no opportunity to keep up with the

sector’s technical evolution.

Nocivelli came from a completely different background, and soon embarked on a restructuring project to restore pride and competitiveness at

Marelli**. Many viewed his arrival with hostility, while others saw it as a breath of

fresh air. His entrepreneurial style revolved around dedication, skill and

practicality. He wanted to create a system that could combine machines for producing energy with

those for transforming it into electricity and transporting it to consumers. His aim was to enhance Italy’s fragmented electromechanical industry and allow it to

successfully compete on an international stage. He expanded the range of products and put systems

competences into place. He entered the market for power lines and increasingly looked beyond national

confines to identify new markets, along with opportunities for larger orders. He also focused on nuclear

energy, which he viewed as being vital for the nation’s growth.

Nocivelli came from a completely different background, and soon embarked on a restructuring project to restore pride and competitiveness at

Marelli**. Many viewed his arrival with hostility, while others saw it as a breath of

fresh air. His entrepreneurial style revolved around dedication, skill and

practicality. He wanted to create a system that could combine machines for producing energy with

those for transforming it into electricity and transporting it to consumers. His aim was to enhance Italy’s fragmented electromechanical industry and allow it to

successfully compete on an international stage. He expanded the range of products and put systems

competences into place. He entered the market for power lines and increasingly looked beyond national

confines to identify new markets, along with opportunities for larger orders. He also focused on nuclear

energy, which he viewed as being vital for the nation’s growth.

Under the guidance of Nocivelli, Ercole Marelli considerably strengthened its position, reaching a turnover of almost eighty billion lira in 1974 and gathering

orders reaching 130 billion, up 56% from the previous year. However, Luigi Nocivelli’s dream was about to

gace an extremely complex scenario: the start of an oil crisis, a

halt in the first Energy Plan (which had promised to create 20 nuclear power plants in Italy), inflation,

monetary chaos, unemployment and high inflation, armed political movements and terrorism. All of these

factors pushed the country towards the brink of collapse. They were known as the “Leaden Year”, where the actions of the Red Brigades and the heightened

risk of kidnappings added to the industrial crisis. During those

years, the company’s management was under constant threat, a dangerous and difficult time that culminated

with the murder of Renato Briano, the head of human resources at

Ercole Marelli. Briano was killed on the morning of November 12th, 1980 during his commute to work on the

underground in Milan.

In spite of all the efforts made by Luigi and a group of young managers working at his side, the company’s

results continued to prove negative. Ercole Marelli went into receivership, and Luigi Nocivelli yielded

the reins of the electromechanical group in 1981. It was a harsh defeat, largely dictated by the burden of the company’s prior debts and the difficult economic, political and social

situation.

* Historical Index of all the years of the Yearbook R&D of Ufficio

Studi Mediobanca

** Carletto Calcia, Il "mio" Tecnomasio, Alkes, 2016

Every creation is a gift unto the future.

- Albert Camus

from 1981 to 1999:

The electrical appliances empire

After leaving Ercole Marelli, Luigi returned to Verolanuova to dedicate himself full-time to the industrial development of El.Fi.

(ElettroFinanziaria)*, the company the Nocivelli brothers had built to manage

their finances and future acquisitions. The experience he had accumulated over the years at Marelli gave

Luigi a strategic vision and an uncommon

ability when it came to assessing businesses. Luigi’s idea was in fact to expand, mostly externally, with the aim of turning the family

business into a major player in international electrical appliances. By expanding the range, he

would counteract the increasing influence of international groups whilst creating a niche market that

would protected against the rise of bigger players.

His first move was to complement the range of products offered by

adding cooking and washing appliances to those used for refrigeration,

which he did through the company’s first acquisitions:

In 1986, the search for electrical appliances manufacturers of optimal size for an acquisition seemed to yield no further results. The Nocivellis therefore decided to expand their horizons and branch out into sectors that worked with the same technologies and in an assembly-line production approach. They embarked on a second round of acquisitions in quick succession:

In 1992, a unique opportunity suddenly arose: the French government decided to sell France’s leading electrical appliance company. Luigi realised this was the chance they needed to get back into the electrical appliance race, which had seemed too tight to enter until then. He seized the opportunity and within a year carried out two acquisitions that made the company one of the great electrical appliance producers: one in France and a smaller one in Germany.

Each operation formed part of a growth process which followed a particular philosophy. Luigi Nocivelli

endeavoured to create a large system that would be uniform, harmonious and

balanced. He strenuously promoted order, and was a man who instinctively sought to put everything in its rightful place: from the first freezers, he moved on to

fridges before tackling, one by one, every element concetning electrical appliances, with the goal to help

Italian and international families solve the practical problems of everyday life. He saw an overall logic to the industrial archipelago he was assembling, bringing

together competences in design, technology and mechanics. He was becoming one

of Italy’s leading twentieth-century industrialists, but he also remained a technician who loved his factories. This is where ideas were put into

practice, and he was convinced that the image of quality and reliability of his products reflected directly

on his person. In less than a decade, Luigi and Gianfranco had managed to transform a small family business

into one of Europe’s largest electrical appliances manufacturers. By the end of 1993, El.Fi. was at the head of one of the main

groups in the electrical appliance sector, with a strong presence in industrial

refrigeration, heating and air conditioning as well. The group’s total turnove approached 3,500 billion Lire, and managed 12,000

employees**.

Each operation formed part of a growth process which followed a particular philosophy. Luigi Nocivelli

endeavoured to create a large system that would be uniform, harmonious and

balanced. He strenuously promoted order, and was a man who instinctively sought to put everything in its rightful place: from the first freezers, he moved on to

fridges before tackling, one by one, every element concetning electrical appliances, with the goal to help

Italian and international families solve the practical problems of everyday life. He saw an overall logic to the industrial archipelago he was assembling, bringing

together competences in design, technology and mechanics. He was becoming one

of Italy’s leading twentieth-century industrialists, but he also remained a technician who loved his factories. This is where ideas were put into

practice, and he was convinced that the image of quality and reliability of his products reflected directly

on his person. In less than a decade, Luigi and Gianfranco had managed to transform a small family business

into one of Europe’s largest electrical appliances manufacturers. By the end of 1993, El.Fi. was at the head of one of the main

groups in the electrical appliance sector, with a strong presence in industrial

refrigeration, heating and air conditioning as well. The group’s total turnove approached 3,500 billion Lire, and managed 12,000

employees**.Luigi’s plan was ambitious, but he had clear ideas and approached each acquisition with his own empirical method, using a handful of key metrics to help support his strong entrepreneurial instinct, as well as his talent for understanding people and analysing companies by simply watching and listening. The search for opportunities was a complex process divided into three basic phases: identifying the company, assessing it, and carrying out the final negotiation.

The analysis was the heart of the process. It required an examination of the market position, customer base, organisational abilities and managerial levels of the company. Any hidden limitations had to be identified through a lucid approach, along with an analysis of the standard of human and technical integration elementes linking the target company to those in El.Fi.: all of these factors were far more important than the purchasing price and accounting figures.

The years between 1993 and 1998 were dedicated to rationalising the group. Three divisions were created: Electrical Appliances, Heating and Air Conditioning, and Commercial Refrigeration.

The Commercial Refrigeration sector continued its series of acquisitions:

In the Heating and Air Conditioning sector, the situation proved more complicated: the critical size proved harder to achieve, and the Nocivelli family decided to dispose of the Heating sector. In 1997, they sold off Chaffoteaux et Maury to the Preussac group, and in 1999 they sold Ocean Idroclima to the Baxi group.

The Electrical Appliances sector saw the company pull off a far-sighted yet complicated acquisition: in 1999 Polar (Poland) joined the group. The company had considerable potential but absorbed a great deal of the group’s energy, due to technically obsolete equipment.

* Historical Index of all the years of the Yearbook R&S of Ufficio Studi Mediobanca

** "I fratelli doppio Bianco" - La Repubblica, July, 8th 1988

It is love, not reason, that is stronger than death.

- Thomas Mann

years 2000's:

The last project

Following the acquisition of Thompson-Brandt, Luigi Nocivelli’s popularity

in France increased, as did his standing amongst industrialists and politicians. It was an ascent

which culminated in 1998, when he was awarded a knighthood of the

Legion of Honour on July 13th at the Ministry for Cooperation in

Paris*. During the course of the ceremony, the possibility that the brothers might

make major new acquisitions, aiming to turn around other ailing French companies, was revealed.

Luigi Nocivelli pursued a plan he had in mind since his days at Marelli: creating a coherent, integrated system of multinational companies that would communicate with

and complement one another, diversifying risks and maximising profits. The acquisitions made throughout

the previous twenty years had built the foundation of a European electrical

appliances hub that would enter the homes of as many consumers as possible, offering products

across refrigeration, cooking and washing. The only missing pieces of the puzzle were small electrical appliances.

Moulinex seemed to be that missing piece: whilst it was a very large,

well-known company, it was clearly struggling. The Russian crisis and the opening of China’s economy,

which was on the road to becoming the world’s main producer of small electrical appliances, had knocked

Moulinex sideways and seriously damaged its accounts. Moulinex was also a complex company with numerous

branches, which clouded its transparency. The fact it was also publicly present on the stock exchange made

a clear and proper assessment even harder. Luigi Nocivelli decided to buy a

small shareholding company to begin his analysis**. During the same period he

developed health problems in the form of cancer, and had to undergo surgery. The illness forced him to

accept that his strength and time were not limitless. In 2000 the

buy-out of the French group continued, and El.Fi. acquired 26.5% of Moulinex. Its aim was to assess the value of Moulinex and

Brandt, align the companies and later merge them. Luigi tried to speed up negotiations, not least because

there was a clear problem of succession in the Brescia-based group where his children and grandchildren

worked. In spite of the scepticism of Gianfranco, some family members and part of his closest co-workers,

Luigi Nocivelli was convinced that the Moulinex deal should go through, and that it was the ideal solution

to make room for each member of the family, with an added possibility of taking the company

public.

Once again Luigi wanted to undertake a detailed due diligence, but as

the company was listed on the stock exchange this would not possible without seriously damaging the

company’s image. At that point, he decided to trust his instinct, just as he had many times before: he

sped things up, abandoned his plans to look into the company and signed a preliminary letter of intent for

the merger. When the agreement was reached at the end of the year,

Luigi presented a three-year restructuring plan which aimed to reach a

turnover of 6,000 billion Lire. The programme involved cutting around 2,000 jobs, and confirmed

that all the production plants would be kept, although they would require further investment to modernise

them.

His ideas were clear, but the strength needed to put them into practice was no longer what it had once

been. Luigi Nocivelli decided to hand management over to the French,

limiting his role as that of main shareholder whilst leaving full powers to the Managing Director. But the

situation was already a serious one: the steps taken by the new

Managing Director, who proposed a plan deemed insufficient to set the books straight, generated new

concerns in the financial community. The company’s shares suffered on the

stock exchange, and the situation collapsed when French banks withdrew the credit lines. In September 2001, Managing Director Patrick Puy presented the account books to the

court. The fallout from the crisis proved to be devastating, not least within the Nocivelli

family: the two brothers, who had worked together throughout their lives, grew apart***.

Luigi did all he could to resume his everyday life. He dedicated himself to the trial in the French

courts and went back to work, driven by the grit and perseverance

he had kept in every situation. He soon decided to embark on a new business venture, to reaffirm his honesty and worth as an individual even more than as an

industrialist. The trial dragged on, and the trustees made a variety of accusations: in 2004 Pierre Blayau, the Managing Director of Moulinex prior to the merger

with Brandt, was accused of embezzlement, bankruptcy and false accounting, guilty of failing to declare the bankruptcy of Moulinex when he was still

responsible for it. Patrick Puy was also incriminated, along with

five other top managers, for similar offences. For their part, Luigi and Gianfranco had to answer for an

apparent shortfall in available funds in Brandt, but they had no problems proving that those had been

needed to realign the two businesses prior to the merger. After years of hearings, the truth emerged in

all its simplicity: the Nocivelli Family was completely acquitted at the

end of the trial on February 12th, 2015. It was an important moral victory for the family that

had lost in the Moulinex venture its entire electrical appliance division, a company which in 1999 had

reached a turnover of 1,300 Milion Euro, with a net result of 32 Million Euro.

* Décret du 13 juillet 1998 portant promotion et nomination au

grade de chevalier

** "La saga des amoureux de robots ménagers. Le clan Nocivelli,

prétendant à l'achat de Moulinex, cultive le mystère autour de lui" - liberation.fr 7 aprile

2000

*** "Brandt offre un nouveau départ à Moulinex" - lsa-conso.fr 14

september 2000

Although the soul quivers at the memory and shies away from weeping, I shall begin.

- Virgilio

from 2002:

The rebirth

Following the bankruptcy of Moulinex-Brandt, Luigi Nocivelli turned to Sergio

Chiostri, his friend and a manager with considerable experience. In 2002, Chiostri had started to analyse the

situation and had realised that the main problem had been to buy Moulinex

without first creating a team of managers to handle the operation

locally. In the past, Luigi Nocivelli had always controlled every aspect of each acquisition in person.

Yet this time, even though it was the most complex and risky buyout of all, he hadn’t managed to keep the

same control of events. Chiostri’s lucid analysis proved that the group controlled by El.Fi. could not be re-established as a whole. It was necessary to keep

the healthy branches alive, and start again from those. The first thing to be done was to divide the activities within the family. Chiostri had been the missing

link, and with his help Luigi and Gianfranco reached an agreement to separate the air conditioning sector from refrigeration. Paolo Nocivelli, Gianfranco’s son, took over management of

Argo and Filiberti. The commercial refrigeration remained in the hands of Luigi and his son Marco, who since January 2000 had become Managing Director of Costan.

During this stage of his rebirth, the Moulinex affair had a profound effect

on Luigi, although it did not damage his links with life itself and with the business. The idea

of stopping work to retire was an option he did not even consider. He trusted Sergio Chiostri’s experience

and, looking to the future, the skills of his son Marco. He worked with them on the strategic development

of a new company, which he imagined as the sum of Costan, Bonnet Névé, New

Market, BKT and George Barker coming together to create a far-reaching, well-structured group

that would develop the commercial refrigeration sector in full. By

identifying the mistakes of the past and pushing to always better himself, Luigi rebuilt his reputation as

a businessman.

Throughout the cold chain market, the different El.Fi. companies were autonomous; the only coordination

was of a financial nature. This approach had always been the one adopted by Luigi and Gianfranco

Nocivelli, and was the one favoured by their group, which was governed by the family’s financial company.

Chiostri was the one who outlined a new vision, and suggested an

alternative organisational model upon which the new setup would be

founded. Luigi called it Epta (the Greek number seven), building the

new venture around the symbolic value of his family and his seven

children. The operating holding was set up in Milan. Luigi

Nocivelli was the chairman and set out the strategic policies, whilst Sergio Chiostri became Managing Director*. It was a

radical change of approach and one Luigi Nocivelli adapted to very quickly, thereby managing to seize the

right moment for to hand over the reins. The company had a slow start

in 2003, but the trend soon inverted**. Luigi, who had always been at

the helm of a network of autonomous companies, now governed a centralised system, whose solidity was built

on the width of the group’s base and a diversification of risk, thanks to a presence across a variety of

markets and geographies.

Throughout the cold chain market, the different El.Fi. companies were autonomous; the only coordination

was of a financial nature. This approach had always been the one adopted by Luigi and Gianfranco

Nocivelli, and was the one favoured by their group, which was governed by the family’s financial company.

Chiostri was the one who outlined a new vision, and suggested an

alternative organisational model upon which the new setup would be

founded. Luigi called it Epta (the Greek number seven), building the

new venture around the symbolic value of his family and his seven

children. The operating holding was set up in Milan. Luigi

Nocivelli was the chairman and set out the strategic policies, whilst Sergio Chiostri became Managing Director*. It was a

radical change of approach and one Luigi Nocivelli adapted to very quickly, thereby managing to seize the

right moment for to hand over the reins. The company had a slow start

in 2003, but the trend soon inverted**. Luigi, who had always been at

the helm of a network of autonomous companies, now governed a centralised system, whose solidity was built

on the width of the group’s base and a diversification of risk, thanks to a presence across a variety of

markets and geographies.

In spite of discovering a mesothelioma, a form of cancer in the lungs, in 2004, Luigi Nocivelli remained

an active and determined man who carefully oversaw the growth of Epta right up until his death in December 2006. Luigi Nocivelli’s Epta is led today by his son Marco,

boasting a turnover in excess of 800 million Euro in 2016, 4,000

employees, sales offices in 35 countries and an output of 200,000 units per year.

For more details, visit: https://www.eptarefrigeration.com/it

* "I Nocivelli tornano a regnare sul 'freddo'" - La Repubblica,

September 15th 2008

** "Dall'Asia al Sudamerica il ritorno dei Nocivelli, imprenditori

globalizzati" - brescia.corriere.it, January 19th 2012